Her Majesty's Theatre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Her Majesty's Theatre is a

The end of the 17th century was a period of intense rivalry amongst London's actors, and in 1695 there was a split in the

The end of the 17th century was a period of intense rivalry amongst London's actors, and in 1695 there was a split in the

Arthur Lloyd. accessed 17 December 2007 The first new play performed was '' After 1709, the theatre was devoted to Italian opera and was sometimes known informally as the Haymarket Opera House.Allingham, Philip V. (Faculty of Education, Lakehead University (Canada)) ''Theatres in Victorian London''.

After 1709, the theatre was devoted to Italian opera and was sometimes known informally as the Haymarket Opera House.Allingham, Philip V. (Faculty of Education, Lakehead University (Canada)) ''Theatres in Victorian London''.

9 May 2007. Victorian Web, accessed 1 June 2007 Young In 1778, the lease for the theatre was transferred from

In 1778, the lease for the theatre was transferred from

Taylor completed a new theatre on the site in 1791. Michael Novosielski had again been chosen as architect for the theatre on an enlarged site, but the building was described by Malcolm in 1807 as

Taylor completed a new theatre on the site in 1791. Michael Novosielski had again been chosen as architect for the theatre on an enlarged site, but the building was described by Malcolm in 1807 as

The first public performance of opera in the new theatre took place on 26 January 1793, the dispute with the Lord Chamberlain over the licence having been settled. This theatre was, at that time, the largest in England, and it became the home of the

The first public performance of opera in the new theatre took place on 26 January 1793, the dispute with the Lord Chamberlain over the licence having been settled. This theatre was, at that time, the largest in England, and it became the home of the

Haydn Festival, accessed 21 December 2007 He was feted in London and returned to Vienna in May 1795 with 12,000 florins. With the departure of the Drury Lane company in 1794, the theatre returned to opera, hosting the first London performances of In 1797, he was elected as member of Parliament for

In 1797, he was elected as member of Parliament for

In 1828, Ebers was succeeded as theatre manager by Pierre François Laporte, who held the position (with a brief gap in 1831–33) until his death in 1841. Two of Rossini's Paris operas (''

In 1828, Ebers was succeeded as theatre manager by Pierre François Laporte, who held the position (with a brief gap in 1831–33) until his death in 1841. Two of Rossini's Paris operas (''

Laporte died suddenly, and Benjamin Lumley took over the management in 1842, introducing London audiences to Donizetti's late operas, ''

Laporte died suddenly, and Benjamin Lumley took over the management in 1842, introducing London audiences to Donizetti's late operas, ''

From 1862 to 1867, the theatre was managed by

From 1862 to 1867, the theatre was managed by

A third building was constructed in 1868 at a cost of £50,000, within the shell of the old theatre, for Lord Dudley. It was designed by Charles Lee and Sons and their partner, William Pain, and built by George Trollope and Sons. The designers had taken over John Nash's practice on his retirement. The new theatre was designed to be less susceptible to fire, with brick firewalls, iron roof trusses and Dennett's patent gypsum-cement floors. The auditorium had four tiers, with a stage large enough for the greatest spectaculars. For opera, the theatre seated 1,890, and for plays, with the orchestra pit removed, 2,500. As a result of a dispute over the rent between Dudley and Mapleson, and a decline in the popularity of ballet, the theatre remained dark until 1874, when it was sold to a Revivalist Christian group for £31,000.

Mapleson returned to Her Majesty's in 1877 and 1878, after a disastrous attempt to build a 2,000-seat National Opera House on a site subsequently used for the building of

A third building was constructed in 1868 at a cost of £50,000, within the shell of the old theatre, for Lord Dudley. It was designed by Charles Lee and Sons and their partner, William Pain, and built by George Trollope and Sons. The designers had taken over John Nash's practice on his retirement. The new theatre was designed to be less susceptible to fire, with brick firewalls, iron roof trusses and Dennett's patent gypsum-cement floors. The auditorium had four tiers, with a stage large enough for the greatest spectaculars. For opera, the theatre seated 1,890, and for plays, with the orchestra pit removed, 2,500. As a result of a dispute over the rent between Dudley and Mapleson, and a decline in the popularity of ballet, the theatre remained dark until 1874, when it was sold to a Revivalist Christian group for £31,000.

Mapleson returned to Her Majesty's in 1877 and 1878, after a disastrous attempt to build a 2,000-seat National Opera House on a site subsequently used for the building of

The theatre was designed as a symmetrical pair with the Carlton Hotel and restaurant on the adjacent site, now occupied by New Zealand House. The frontage formed three parts, each of nine bays. The hotel occupied two parts, the theatre one, and the two buildings were unified by a cornice above the ground floor. The buildings rose to four storeys, with attic floors above, surmounted by large squared domes in a style inspired by the

The theatre was designed as a symmetrical pair with the Carlton Hotel and restaurant on the adjacent site, now occupied by New Zealand House. The frontage formed three parts, each of nine bays. The hotel occupied two parts, the theatre one, and the two buildings were unified by a cornice above the ground floor. The buildings rose to four storeys, with attic floors above, surmounted by large squared domes in a style inspired by the

The current theatre opened on 28 April 1897. Herbert Beerbohm Tree built the theatre with profits from his tremendous success at the Haymarket Theatre, and he owned, managed and lived in the theatre from its construction until his death in 1917. For his personal use, he had a banqueting hall and living room installed in the massive, central, square French-style dome. This building did not specialise in opera, although there were some operatic performances in its early years. The theatre opened with a dramatisation of Gilbert Parker's ''The Seats of the Mighty''. Adaptations of novels by Dickens, Tolstoy, and others formed a significant part of the repertoire, along with classical works from Molière and

The current theatre opened on 28 April 1897. Herbert Beerbohm Tree built the theatre with profits from his tremendous success at the Haymarket Theatre, and he owned, managed and lived in the theatre from its construction until his death in 1917. For his personal use, he had a banqueting hall and living room installed in the massive, central, square French-style dome. This building did not specialise in opera, although there were some operatic performances in its early years. The theatre opened with a dramatisation of Gilbert Parker's ''The Seats of the Mighty''. Adaptations of novels by Dickens, Tolstoy, and others formed a significant part of the repertoire, along with classical works from Molière and

PeoplePlayUK, accessed 12 February 2008. Tree's productions were known for their elaborate and spectacular scenery and effects, often including live animals and real grass. These remained both popular and profitable, but in his last decade, Tree's acting style was seen as increasingly outmoded, and many of his plays received bad reviews. Tree defended himself from critical censure, demonstrating his continuing popularity at the box office until his death. In 1904, Tree founded the Academy of Dramatic Art (later Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, RADA), which spent a year based in the theatre before moving in 1905 to Gower Street (London), Gower Street in Bloomsbury Publishing, Bloomsbury. Tree continued to take graduates of the Academy into his company at His Majesty's, employing some 40 actors in this way by 1911.

The facilities of the theatre naturally lent themselves to the new genre of musical theatre, and Percy Fletcher was appointed musical director in 1915, a post he held for the next 17 years until his death. ''

In 1904, Tree founded the Academy of Dramatic Art (later Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, RADA), which spent a year based in the theatre before moving in 1905 to Gower Street (London), Gower Street in Bloomsbury Publishing, Bloomsbury. Tree continued to take graduates of the Academy into his company at His Majesty's, employing some 40 actors in this way by 1911.

The facilities of the theatre naturally lent themselves to the new genre of musical theatre, and Percy Fletcher was appointed musical director in 1915, a post he held for the next 17 years until his death. ''

BroadwayWorld.com, 5 October 2011 It is the second longest-running West End musical in history (after ''Les Misérables (musical), Les Misérables''). In a sign of its continuing popularity, ''Phantom'' ranked second in a 2006 BBC Radio 2 listener poll of the "Nation's Number One Essential Musicals". The musical is also the longest-running show on Broadway theatre, Broadway, was made into a The Phantom of the Opera (2004 film), film in 2004 and had been seen by over 130 million people in 145 cities in 27 countries and grossed more than £3.2bn ($5bn) by 2011, the most successful entertainment project in history. Her Majesty's Theatre's "grand exterior" and "luxurious interior, with its three tiers of boxes and gold statuary around the stage", as well as French Renaissance design, "make it an ideal site for this Gothic tale" set at the Opéra Garnier. The original Victorian era, Victorian stage machinery remains beneath the stage of the theatre. Designer Maria Björnson found a way to use it "to show the Phantom travelling across the lake as if floating on a sea of mist and fire", in a key scene from the musical. On 5 May 2008, for the first time in the run, the show closed for three days. This allowed the installation of an improved sound system at the theatre, consisting of over of cabling and the siting of 120 auditorium speakers. In March 2020, the production was stopped indefinitely due to the COVID-19 pandemic which closed every West End theatre. The show was resumed on 27 July 2021. The theatre's capacity is 1,216 seats on four levels. Really Useful Group#LW Theatres, Really Useful Theatres Group purchased it in January 2000 with nine other London theatres formerly owned by the Moss Empires, Stoll-Moss Group. Between 1990 and 1993, renovation and improvements were made by the H.L.M. and C. G. Twelves partnership. In 2014, Really Useful Theatres split from the Really Useful Group and owns the theatre.Dennys, Harriet

"Lord Lloyd-Webber splits theatre group to expand on a global stage"

''The Telegraph'', (London) 24 March 2014, accessed 3 October 2014.

* Adams, William Davenport.

* Adams, William Davenport.

''A dictionary of the drama''"> ''A dictionary of the drama''

(1904) Chatto & Windus

* Burden, Michael, "Biagio Rebecca Draws the London Opera House: London’s Kings Theatre in the 1790s", in ''The Burlington'', 161 (May 2019), pp. 364–373. * Burden, Michael, "London's Opera House in Colour 1705–1844, with Diversions in Fencing, Masquerading, and a visit from Elisabeth Félix", in ''Music in Art '', 44/1–2: "Dance & Image" (Spring–Fall 2019), pp. 19–165. * Burden, Michael, "Visions of Dance at the King's Theatre; Reconsidering London's 'Opera House'", in ''Music in Art '', 36/1–2: "Dance & Image" (Spring–Fall 2011), pp. 92–116. * Earl, John and Michael Sell. ''Guide to British Theatres 1750–1950'', pp. 116–17 (Theatres Trust, 2000) * Larkin, Colin (ed). ''Guinness Who's Who of Stage Musicals'' (Guinness Publishing, 1994) * Parker, John (ed). ''Who's Who in the Theatre'', tenth edition, revised, London, 1947, p. 1184.

Her Majesty's Theatre profile

at Society of London Theatre#Official London Theatre website and Official London Theatre Guide, OfficialLondonTheatre.com

Her Majesty's Theatre profile

at Playbill, Playbill.com *

Video of the theatre and environs after a 2012 performance

{{Use dmy dates, date=July 2019 West End theatres 1705 establishments in England Theatres completed in 1705 Theatres completed in 1897 Theatres in the City of Westminster Fires in London Grade II* listed buildings in the City of Westminster Grade II* listed theatres Opera houses in England Ballet in London Charles J. Phipps buildings

West End theatre

West End theatre is mainstream professional theatre staged in the large theatres in and near the West End of London.Christopher Innes, "West End" in ''The Cambridge Guide to Theatre'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 1194–1 ...

situated on Haymarket Haymarket may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Haymarket, New South Wales, area of Sydney, Australia

Germany

* Heumarkt (KVB), transport interchange in Cologne on the site of the Heumarkt (literally: hay market)

Russia

* Sennaya Square (''Hay Squ ...

in the City of Westminster

The City of Westminster is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and London boroughs, borough in Inner London. It is the site of the United Kingdom's Houses of Parliament and much of the British government. It occupies a large area of cent ...

, London. The present building was designed by Charles J. Phipps

Charles John Phipps (25 March 1835 – 25 May 1897) was an English architect best known for his more than 50 theatres built in the latter half of the 19th century, including several important London theatres. He is also noted for his design of ...

and was constructed in 1897 for actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree (17 December 1852 – 2 July 1917) was an English actor and theatre manager.

Tree began performing in the 1870s. By 1887, he was managing the Haymarket Theatre in the West End, winning praise for adventurous progra ...

, who established the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA; ) is a drama school in London, England, that provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in the Bloomsbury area of Central London, close to the Sen ...

at the theatre. In the early decades of the 20th century, Tree produced spectacular productions of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and other classical works, and the theatre hosted premieres by major playwrights such as George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, J. M. Synge

Edmund John Millington Synge (; 16 April 1871 – 24 March 1909) was an Irish playwright, poet, writer, collector of folklore, and a key figure in the Irish Literary Revival. His best known play ''The Playboy of the Western World'' was poorly r ...

, Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time'' magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combination of cheek and ...

and J. B. Priestley

John Boynton Priestley (; 13 September 1894 – 14 August 1984) was an English novelist, playwright, screenwriter, broadcaster and social commentator.

His Yorkshire background is reflected in much of his fiction, notably in ''The Good Compa ...

. Since the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the wide stage has made the theatre suitable for large-scale musical productions, and the theatre has accordingly specialised in hosting musicals. The theatre has been home to record-setting musical theatre runs, notably the First World War sensation ''Chu Chin Chow

''Chu Chin Chow'' is a musical comedy written, produced and directed by Oscar Asche, with music by Frederic Norton, based (with minor embellishments) on the story of ''Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves''. Gänzl, Kurt"''Chu Chin Chow'' Musical Tale of ...

''Larkin, Colin (ed). ''Guinness Who's Who of Stage Musicals'' (Guinness Publishing, 1994) and the current (June 2022) production of Andrew Lloyd Webber

Andrew Lloyd Webber, Baron Lloyd-Webber (born 22 March 1948), is an English composer and impresario of musical theatre. Several of his musicals have run for more than a decade both in the West End and on Broadway. He has composed 21 musicals, ...

's ''The Phantom of the Opera

''The Phantom of the Opera'' (french: Le Fantôme de l'Opéra) is a novel by French author Gaston Leroux. It was first published as a serial in from 23 September 1909 to 8 January 1910, and was released in volume form in late March 1910 by Pierr ...

'', which previously played continuously at Her Majesty's between 1986 and March 2020.

The theatre was established by architect and playwright John Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restora ...

, in 1705, as the Queen's Theatre. Legitimate drama unaccompanied by music was prohibited by law in all but the two London patent theatres, and so this theatre quickly became an opera house

An opera house is a theatre building used for performances of opera. It usually includes a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, and backstage facilities for costumes and building sets.

While some venues are constructed specifically for o ...

. Between 1711 and 1739, more than 25 operas by George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque music, Baroque composer well known for his opera#Baroque era, operas, oratorios, anthems, concerto grosso, concerti grossi, ...

premiered here. Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

’s series of concerts in London took place here in the 1790s. In the early 19th century, the theatre hosted the opera company that was to move to the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal O ...

, in 1847, and presented the first London performances of Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

's ''La clemenza di Tito

' (''The Clemency of Titus''), K. 621, is an '' opera seria'' in two acts composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Caterino Mazzolà, after Pietro Metastasio. It was started after most of ' (''The Magic Flute''), the last of ...

'', ''Così fan tutte

(''All Women Do It, or The School for Lovers''), K. 588, is an opera buffa in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. It was first performed on 26 January 1790 at the Burgtheater in Vienna, Austria. The libretto was written by Lorenzo Da Ponte w ...

'' and ''Don Giovanni

''Don Giovanni'' (; K. 527; Vienna (1788) title: , literally ''The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni'') is an opera in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. Its subject is a centuries-old Spanis ...

''. It also hosted the Ballet of her Majesty's Theatre in the mid-19th century, before returning to hosting the London premieres of such operas as Bizet

Georges Bizet (; 25 October 18383 June 1875) was a French composer of the Romantic era. Best known for his operas in a career cut short by his early death, Bizet achieved few successes before his final work, ''Carmen'', which has become on ...

's ''Carmen

''Carmen'' () is an opera in four acts by the French composer Georges Bizet. The libretto was written by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, based on the Carmen (novella), novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. The opera was first perfo ...

'' and Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's ''Ring Cycle

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the ''Nibelung ...

''. The theatre has also been known as Queen's Theatre at the Haymarket, prior to being renamed Her Majesty's Theatre.

The name of the theatre changes with the gender of the monarch. It first became the King's Theatre in 1714 on the accession of George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George I of Antioch (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgor ...

. It was renamed Her Majesty's Theatre in 1837. Most recently, the theatre was known as His Majesty's Theatre from 1901 to 1952, and it became Her Majesty's on the accession of Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

. The theatre's capacity is 1,216 seats, and the building was Grade II* listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

by English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

in 1970. LW Theatres

The Really Useful Group Ltd. (RUG) is an international company set up in 1977 by Andrew Lloyd Webber. It is involved in theatre, film, television, video and concert productions, merchandising, magazine publishing, records and music publishing. ...

has owned the building since 2000. The land beneath it is on a long-term lease from the Crown Estate

The Crown Estate is a collection of lands and holdings in the United Kingdom belonging to the British monarch as a corporation sole, making it "the sovereign's public estate", which is neither government property nor part of the monarch's priva ...

. Following the accession of Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

in September 2022, LW Theatres confirmed the theatre's name will revert to His Majesty's Theatre, after the coronation of the new king.

History

The end of the 17th century was a period of intense rivalry amongst London's actors, and in 1695 there was a split in the

The end of the 17th century was a period of intense rivalry amongst London's actors, and in 1695 there was a split in the United Company

The United Company was a London theatre company formed in 1682 with the merger of the King's Company and the Duke's Company.

Both the Duke's and King's Companies suffered poor attendance during the turmoil of the Popish Plot period, 1678&ndas ...

, who had a monopoly on the performance of drama at their two theatres. Dramatist and architect John Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restora ...

saw this as an opportunity to break the duopoly of the patent theatres, and in 1703 he acquired a former stable yard, at a cost of £2,000, for the construction of a new theatre on the Haymarket. In the new business, he hoped to improve the share of profits that would go to playwrights and actors. He raised the money by subscription, probably amongst members of the Kit-Cat Club

The Kit-Cat Club (sometimes Kit Kat Club) was an early 18th-century English club in London with strong political and literary associations. Members of the club were committed Whigs (British political party), Whigs. They met at the Trumpet tavern ...

:

To recover them hat_is,_Thomas_Betterton's_company.html" ;"title="Thomas_Betterton.html" ;"title="hat is, Thomas Betterton">hat is, Thomas Betterton's company">Thomas_Betterton.html" ;"title="hat is, Thomas Betterton">hat is, Thomas Betterton's company therefore, to their due Estimation, a new Project was form'd of building them a stately theatre in the Hay-Market, by Sir John Vanbrugh, for which he raised a Subscription of thirty Persons of Quality, at one hundred Pounds each, in Consideration whereof every Subscriber, for his own Life, was to be admitted to whatever Entertainments should be publickly perform'd there, without farther Payment for his Entrance. —John Vanbrugh's notice of subscription for the new theatre"The Haymarket Opera House"He was joined in the enterprise by his principal associate and manager William Congreve and an actors' co-operative led by Thomas Betterton. The theatre provided the first alternative to the

''Survey of London: volumes 29 and 30: St James Westminster''. Part 1 (1960). pp. 223–50. accessed 18 December 2007

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

, built in 1663 and the Lincoln's Inn Fields, Lincoln's Inn, founded in 1660 (forerunner of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal O ...

, built in 1728). The theatre's site is the second oldest such site in London that remains in use. These three post- English Interregnum, interregnum theatres defined the shape and use of modern theatres.. Sadler's Wells Theatre

Sadler's Wells Theatre is a performing arts venue in Clerkenwell, London, England located on Rosebery Avenue next to New River Head. The present-day theatre is the sixth on the site since 1683. It consists of two performance spaces: a 1,500-seat ...

was founded as a music room in 1683, and a theatre was built on the site in 1765.

Vanbrugh's theatre: 1705–1789

The land for the theatre was held on a lease renewable in 1740 and was ultimately owned, as it is today, by theCrown Estate

The Crown Estate is a collection of lands and holdings in the United Kingdom belonging to the British monarch as a corporation sole, making it "the sovereign's public estate", which is neither government property nor part of the monarch's priva ...

. Building was delayed by the necessity of acquiring the street frontage, and a three bay entrance led to a brick shell long and wide. Colley Cibber

Colley Cibber (6 November 1671 – 11 December 1757) was an English actor-manager, playwright and Poet Laureate. His colourful memoir ''Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber'' (1740) describes his life in a personal, anecdotal and even rambling ...

described the audience fittings as lavish but the facilities for playing poor.

Vanbrugh and Congreve received Queen Anne's authority to form ''a Company of Comedians'' on 14 December 1704, and the theatre opened as the Queen's Theatre on 9 April 1705 with imported Italian singers in ''Gli amori d'Ergasto'' (''The Loves of Ergasto''), an opera by Jakob Greber

Johann Jakob Greber (? – buried 5 July 1731) was a German Baroque composer and musician. His first name sometimes appeared in its Italianized version, Giacomo, especially during the years he spent in London (1702 – 1705). Greber composed solo ...

, with an epilogue by Congreve. This was the first Italian opera performed in London. The opera failed, and the season struggled on through May, with revivals of plays and operas."Her Majesty's Theatre"Arthur Lloyd. accessed 17 December 2007 The first new play performed was ''

The Conquest of Spain

''The Conquest of Spain'' is a 1705 tragedy by the English writer Mary Pix. The play was published anonymously, but has been widely attributed to Pix. It was a reworking of the Jacobean tragedy ''All's Lost by Lust'' by William Rowley. It was t ...

'' by Mary Pix

Mary Pix (1666 – 17 May 1709) was an English novelist and playwright. As an admirer of Aphra Behn and colleague of Susanna Centlivre, Pix has been called "a link between women writers of the Restoration and Augustan periods".

Early years

...

. The theatre proved too large for actors' voices to carry across the auditorium, and the first season was a failure. Congreve departed, Vanbrugh bought out his other partners, and the actors reopened the Lincoln's Inn Fields' theatre in the summer. Although early productions combined spoken dialogue with incidental music, a taste was growing amongst the nobility for Italian opera

Italian opera is both the art of opera in Italy and opera in the Italian language. Opera was born in Italy around the year 1600 and Italian opera has continued to play a dominant role in the history of the form until the present day. Many famous ...

, which was completely sung, and the theatre became devoted to opera. As he became progressively more involved in the construction of Blenheim Palace, Vanbrugh's management of the theatre became increasingly chaotic, showing "numerous signs of confusion, inefficiency, missed opportunities, and bad judgement". On 7 May 1707, experiencing mounting losses and running costs, Vanbrugh was forced to sell a lease on the theatre for fourteen years to Owen Swiny

Owen Swiny (Also spelled McSwiny, Swiney, MacSwiny or MacSwinny) (1676, near Enniscorthy, Ireland – 2 October 1754) was an Irish theatre impresario and art dealer active in London known for his work in popularising Italian opera in London ...

at a considerable loss. In December of that year, the Lord Chamberlain's Office

The Lord Chamberlain's Office is a department within the British Royal Household. It is concerned with matters such as protocol, state visits, investitures, garden parties, royal weddings and funerals. For example, in April 2005 it organised the ...

ordered that "all Operas and other Musicall presentments be performed for the future only at Her Majesty's Theatre in the Hay Market" and forbade the performance of further non-musical plays there.

After 1709, the theatre was devoted to Italian opera and was sometimes known informally as the Haymarket Opera House.Allingham, Philip V. (Faculty of Education, Lakehead University (Canada)) ''Theatres in Victorian London''.

After 1709, the theatre was devoted to Italian opera and was sometimes known informally as the Haymarket Opera House.Allingham, Philip V. (Faculty of Education, Lakehead University (Canada)) ''Theatres in Victorian London''.9 May 2007. Victorian Web, accessed 1 June 2007 Young

George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque music, Baroque composer well known for his opera#Baroque era, operas, oratorios, anthems, concerto grosso, concerti grossi, ...

produced his English début, ''Rinaldo

Rinaldo may refer to:

*Renaud de Montauban (also spelled Renaut, Renault, Italian: Rinaldo di Montalbano, Dutch: Reinout van Montalbaen, German: Reinhold von Montalban), a legendary knight in the medieval Matter of France

* Rinaldo (''Jerusalem Lib ...

'', on 24 February 1711 at the theatre, featuring the two leading castrati

A castrato (Italian, plural: ''castrati'') is a type of classical male singing voice equivalent to that of a soprano, mezzo-soprano, or contralto. The voice is produced by castration of the singer before puberty, or it occurs in one who, due to ...

of the era, Nicolo Grimaldi and Valentino Urbani

Valentino Urbani (born in Udine; ''fl.'' 1690–1722) was an Italian mezzo-soprano or alto castrato who sang for the composer George Frideric Handel in the 18th century. He was known by the stage name Valentini. He sang the role of Eustazio at t ...

. This was the first Italian opera composed specifically for the London stage. The work was well received, and Handel was appointed resident composer for the theatre, but losses continued, and Swiney fled abroad to escape his creditors. John James Heidegger

John James (Johann Jacob) Heidegger (19 June 1666 – 5 September 1749) was a Swiss count and leading impresario of masquerades in the early part of the 18th century.

The son of Zürich clergyman Johann Heinrich Heidegger, Johann Jacob Heidegger ...

took over the management of the theatre and, from 1719, began to extend the stage through arches into the houses to the south of the theatre. A "Royal Academy of Music" was formed by subscription from wealthy sponsors, including the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, to support Handel's productions at the theatre. Under this sponsorship, Handel conducted a series of more than 25 of his original operas, continuing until 1739 Handel was also a partner in the management with Heidegger from 1729 to 1734, and he contributed to incidental music for theatre, including for a revival of Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

's ''The Alchemist

An alchemist is a person who practices alchemy.

Alchemist or Alchemyst may also refer to:

Books and stories

* ''The Alchemist'' (novel), the translated title of a 1988 allegorical novel by Paulo Coelho

* ''The Alchemist'' (play), a play by Be ...

'', opening on 14 January 1710.

On the accession of George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George I of Antioch (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgor ...

in 1714, the theatre was renamed the King's Theatre and remained so named during a succession of male monarchs who occupied the throne. At this time only the two patent theatres were permitted to perform serious drama in London, and lacking letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

, the theatre remained associated with opera. In 1762, Johann Christian Bach

Johann Christian Bach (September 5, 1735 – January 1, 1782) was a German composer of the Classical period (music), Classical era, the eighteenth child of Johann Sebastian Bach, and the youngest of his eleven sons. After living in Italy for ...

travelled to London to premiere three operas at the theatre, including ''Orione'' on 19 February 1763. This established his reputation in England, and he became music master to Queen Charlotte

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Sophia Charlotte; 19 May 1744 – 17 November 1818) was Queen of Great Britain and of Ireland as the wife of King George III from their marriage on 8 September 1761 until the union of the two kingdoms ...

.

In 1778, the lease for the theatre was transferred from

In 1778, the lease for the theatre was transferred from James Brook

James William Brook (1 February 1897 – 3 March 1989) was an English first-class cricketer, who played one match for Yorkshire against Glamorgan at Bramall Lane, Sheffield in 1923.

Born in Ossett, Yorkshire, England, Brook was a right-handed ...

to Thomas Harris

William Thomas Harris III (born 1940/1941) is an American writer, best known for a series of suspense novels about his most famous character, Hannibal Lecter. The majority of his works have been adapted into films and television, the most notab ...

, stage manager of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal O ...

, and to the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 17517 July 1816) was an Irish satirist, a politician, a playwright, poet, and long-term owner of the London Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. He is known for his plays such as ''The Rivals'', ''The Sc ...

for £22,000. They paid for the remodelling of the interior by Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him. With his o ...

in the same year. In November 1778, ''The Morning Chronicle

''The Morning Chronicle'' was a newspaper founded in 1769 in London. It was notable for having been the first steady employer of essayist William Hazlitt as a political reporter and the first steady employer of Charles Dickens as a journalist. It ...

'' reported that Harris and Sheridan had

... at a considerable expence, almost entirely new built the audience part of the house, and made a great variety of alterations, part of which are calculated for the rendering the theatre more light, elegant and pleasant, and part for the ease and convenience of the company. The sides of the frontispiece are decorated with two figures painted byThe expense of the improvements was not matched by the box office receipts, and the partnership dissolved, with Sheridan buying out his partner with a mortgage on the theatre of £12,000 obtained from the bankerGainsborough Gainsborough or Gainsboro may refer to: Places * Gainsborough, Ipswich, Suffolk, England ** Gainsborough Ward, Ipswich * Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, a town in England ** Gainsborough (UK Parliament constituency) * Gainsborough, New South Wales, ..., which are remarkably picturesque and beautiful; the heavy columns which gave the house so gloomy an aspect that it rather resembled a large mausoleum or a place for funeral dirges, than a theatre, are removed. —November 1778, ''The Morning Chronicle ''The Morning Chronicle'' was a newspaper founded in 1769 in London. It was notable for having been the first steady employer of essayist William Hazlitt as a political reporter and the first steady employer of Charles Dickens as a journalist. It ...''

Henry Hoare

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

.

One member of the company, Giovanni Gallini

Giovanni Andrea Battista Gallini (born Florence, Italy, 7 January 1728, died London, 5 January 1805), later known as Sir John Andrew Gallini, was an Italian people, Italian dancer, choreographer and impresario who was made a "Knight of the Order o ...

, had made his début at the theatre in 1753 and had risen to the position of dancing master, gaining an international reputation. Gallini had tried to buy Harris' share but had been rebuffed. He now purchased the mortgage. Sheridan quickly became bankrupt after placing the financial affairs of the theatre in the hands of William Taylor, a lawyer. The next few years saw a struggle for control of the theatre and Taylor bought Sheridan's interest in 1781. In 1782 the theatre was remodelled by Michael Novosielski, formerly a scene painter at the theatre. In May 1783, Taylor was arrested by his creditors, and a forced sale ensued, with Harris purchasing the lease and much of the effects. Further legal action transferred the interests in the theatre to a board of trustees, including Novosielski. The trustees acted with a flagrant disregard for the needs of the theatre or other creditors, seeking only to enrich themselves, and in August 1785 the Lord Chamberlain took over the running of the enterprise, in the interests of the creditors. Gallini, meanwhile, had become manager. In 1788, the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

observed "that there appeared in all the proceedings respecting this business, a wish of distressing the property, and that it would probably be consumed in that very court to which ... he interested partiesseemed to apply for relief". Performances suffered, with the box receipts taken by Novosielski, rather than given to Gallini to run the house. Money continued to be squandered on endless litigation or was misappropriated. Gallini tried to keep the theatre going, but he was forced to employ amateur performers. ''The World'' described a performance as follows: "... the dance, if such it can be called was like the movements of heavy cavalry. It was hissed very abundantly."Bondeson, Jan. ''The London Monster: A Sanguinary Tale'' (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000) At other times, Gallini had to defend himself against a dissatisfied audience who charged the stage and destroyed the fittings, as the company ran for their lives.

Fire

The theatre burnt down on 17 June 1789 during evening rehearsals, and the dancers fled the building as beams fell onto the stage. The fire had been deliberately set on the roof, and Gallini offered a reward of £300 for capture of the culprit. With the theatre destroyed, each group laid their own plans for a replacement. Gallini obtained a licence from the Lord Chamberlain to perform opera at the nearby Little Theatre, and he entered into a partnership with R. B. O'Reilly to obtain land inLeicester Fields

Leicester Square ( ) is a pedestrianised square in the West End of London, England. It was laid out in 1670 as Leicester Fields, which was named after the recently built Leicester House, itself named after Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicest ...

for a new building, which too would require a licence. The two quarrelled, and each then planned to wrest control of the venture from the other. The authorities refused to grant either of them a patent for Leicester Fields, but O'Reilly was granted a licence for four years to put on opera at the Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major road in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, running from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch via Oxford Circus. It is Europe's busiest shopping street, with around half a million daily visitors, and as ...

Pantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone S ...

. This too, would burn to the ground in 1792. Meanwhile, Taylor reached an agreement with the creditors of the King's Theatre and attempted to purchase the remainder of the lease from Edward Vanbrugh, but this was now promised to O'Reilly. A further complication arose as the theatre needed to expand onto adjacent land that now came into the possession of a Taylor supporter. The scene was set for a further war of attrition between the lessees, but at this point O'Reilly's first season at the Pantheon failed miserably, and he fled to Paris to avoid his creditors.

By 1720, Vanbrugh's direct connection with the theatre had been terminated, but the leases and rents had been transferred to both his own family and that of his wife's through a series of trusts and benefices, with Vanbrugh himself building a new home in Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

. After the fire, the Vanbrugh family's long association with the theatre was terminated, and all their leases were surrendered by 1792.

Second theatre: 1791–1867

Taylor completed a new theatre on the site in 1791. Michael Novosielski had again been chosen as architect for the theatre on an enlarged site, but the building was described by Malcolm in 1807 as

Taylor completed a new theatre on the site in 1791. Michael Novosielski had again been chosen as architect for the theatre on an enlarged site, but the building was described by Malcolm in 1807 as

fronted by a stone basement in rustic work, with the commencement of a very superb building of the Doric order, consisting of three pillars, two windows, an entablature, pediment, and balustrade. This, if it had been continued, would have contributed considerably to the splendour of London; but the unlucky fragment is fated to stand as a foil to the vile and absurd edifice of brick pieced to it, which I have not patience to describe. —The critic Malcolm, quoted in ''Old and New London'' (1878)The Lord Chamberlain, a supporter of O'Reilly, refused a performing licence to Taylor. The theatre opened on 26 March 1791 with a private performance of song and dance entertainment, but was not allowed to open to the public. The new theatre was heavily indebted and spanned separate plots of land that were leased to Taylor by four different owners on differing terms of revision. As a later manager of the theatre wrote, "In the history of property, there has probably been no parallel instance wherein the legal labyrinth has been so difficult to thread." Meetings were held at

Carlton House

Carlton House was a mansion in Westminster, best known as the town residence of King George IV. It faced the south side of Pall Mall, and its gardens abutted St James's Park in the St James's district of London. The location of the house, no ...

and Bedford House attempting to reconcile the parties. On 24 August 1792 a General Opera Trust Deed was signed by the parties. The general management of the theatre was to be entrusted to a committee of noblemen, appointed by the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, who would then appoint a general manager. Funds would be disbursed from the profits to compensate the creditors of both the King's Theatre and the Pantheon. The committee never met, and management devolved to Taylor.

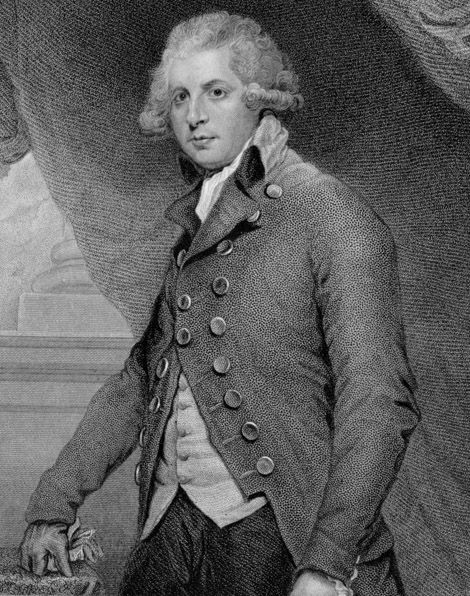

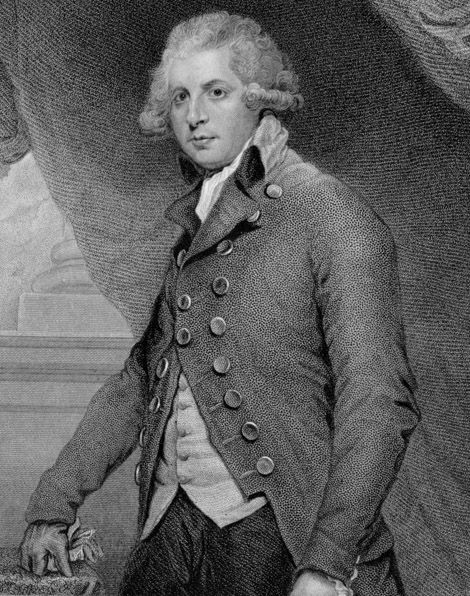

William Taylor

The first public performance of opera in the new theatre took place on 26 January 1793, the dispute with the Lord Chamberlain over the licence having been settled. This theatre was, at that time, the largest in England, and it became the home of the

The first public performance of opera in the new theatre took place on 26 January 1793, the dispute with the Lord Chamberlain over the licence having been settled. This theatre was, at that time, the largest in England, and it became the home of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

company while that company's home theatre was itself rebuilt between 1791–94.

From 1793, seven small houses at the east side of the theatre fronting on the Haymarket were demolished and replaced by a large concert room. It was in this room that Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

gave a series of concerts, under the sponsorship of Johann Peter Salomon

Johann Peter Salomon (20 February 1745 aptized– 28 November 1815) was a German violinist, composer, conductor and musical impresario. Although he was an accomplished violinist, he is best known for bringing Joseph Haydn to London and for c ...

, on his second visit to London in 1794–95. He presented his own symphonies, some of them premieres, conducted by himself, and was paid £50 each for 20 concerts.1791–1795 ''London Journey''.Haydn Festival, accessed 21 December 2007 He was feted in London and returned to Vienna in May 1795 with 12,000 florins. With the departure of the Drury Lane company in 1794, the theatre returned to opera, hosting the first London performances of

Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

's ''La clemenza di Tito

' (''The Clemency of Titus''), K. 621, is an '' opera seria'' in two acts composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Caterino Mazzolà, after Pietro Metastasio. It was started after most of ' (''The Magic Flute''), the last of ...

'' in 1806, ''Così fan tutte

(''All Women Do It, or The School for Lovers''), K. 588, is an opera buffa in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. It was first performed on 26 January 1790 at the Burgtheater in Vienna, Austria. The libretto was written by Lorenzo Da Ponte w ...

'' and ''Die Zauberflöte

''The Magic Flute'' (German: , ), K. 620, is an opera in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to a German libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. The work is in the form of a ''Singspiel'', a popular form during the time it was written that includ ...

'' in 1811, and ''Don Giovanni

''Don Giovanni'' (; K. 527; Vienna (1788) title: , literally ''The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni'') is an opera in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. Its subject is a centuries-old Spanis ...

'' in 1816. Between 1816 and 1818, John Nash and George Repton made alterations to the façade and increased the capacity of the auditorium to 2,500. They also added a shopping arcade

A shopping center (American English) or shopping centre (Commonwealth English), also called a shopping complex, shopping arcade, shopping plaza or galleria, is a group of shops built together, sometimes under one roof.

The first known collec ...

, called the Royal Opera Arcade, which has survived fires and renovations and still exists. It runs along the rear of the theatre. In 1818–20, the British premieres of Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

's operas ''Il barbiere di Siviglia

''The Barber of Seville, or The Useless Precaution'' ( it, Il barbiere di Siviglia, ossia L'inutile precauzione ) is an ''opera buffa'' in two acts composed by Gioachino Rossini with an Italian libretto by Cesare Sterbini. The libretto was base ...

, Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra

''Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra'' (; ''Elizabeth, Queen of England'') is a ''dramma per musica'' or opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to a libretto by Giovanni Schmidt, from the play ''Il paggio di Leicester'' (''Leicester's Page'') by C ...

, L'italiana in Algeri

''L'italiana in Algeri'' (; ''The Italian Girl in Algiers'') is an operatic ''dramma giocoso'' in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to an Italian libretto by Angelo Anelli, based on his earlier text set by Luigi Mosca. It premiered at the Teatro San ...

, La Cenerentola

' (''Cinderella, or Goodness Triumphant'') is an operatic ''dramma giocoso'' in two acts by Gioachino Rossini. The libretto was written by Jacopo Ferretti, based on the libretti written by Charles-Guillaume Étienne for the opera '' Cendrillon'' ...

'' and ''Tancredi

''Tancredi'' is a ''melodramma eroico'' ('' opera seria'' or heroic opera) in two acts by composer Gioachino Rossini and librettist Gaetano Rossi (who was also to write ''Semiramide'' ten years later), based on Voltaire's play ''Tancrède'' (176 ...

'' took place, and the theatre became known as the Italian Opera House, Haymarket by the 1820s.

In 1797, he was elected as member of Parliament for

In 1797, he was elected as member of Parliament for Leominster

Leominster ( ) is a market town in Herefordshire, England, at the confluence of the River Lugg and its tributary the River Kenwater. The town is north of Hereford and south of Ludlow in Shropshire. With a population of 11,700, Leominster is t ...

, a position that gave him immunity from his creditors. When that parliament dissolved in 1802, he fled to France. Later, he returned, and was member of Parliament for Barnstaple

Barnstaple ( or ) is a river-port town in North Devon, England, at the River Taw's lowest crossing point before the Bristol Channel. From the 14th century, it was licensed to export wool and won great wealth. Later it imported Irish wool, bu ...

from 1806 to 1812 while continuing his association with the theatre. Taylor paid little of the agreed receipts to performers, or composers, and lived for much of his period of management in the King's Bench, a debtors' prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Historic ...

in Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

. Here he maintained an apartment next to Lady Hamilton

Dame Emma Hamilton (born Amy Lyon; 26 April 176515 January 1815), generally known as Lady Hamilton, was an English maid, model, dancer and actress. She began her career in London's demi-monde, becoming the mistress of a series of wealthy me ...

and lived in some luxury, entertaining lavishly.

John Ebers

John Ebers, a bookseller, took over the management of the theatre in 1821, and seven more London premieres of Rossini operas (''La gazza ladra

''La gazza ladra'' (, ''The Thieving Magpie'') is a ''melodramma'' or opera semiseria in two acts by Gioachino Rossini, with a libretto by Giovanni Gherardini based on ''La pie voleuse'' by Théodore Baudouin d'Aubigny and Louis-Charles Caigni ...

, Il turco in Italia

''Il turco in Italia'' (English: ''The Turk in Italy'') is an opera buffa in two acts by Gioachino Rossini. The Italian-language libretto was written by Felice Romani. It was a re-working of a libretto by Caterino Mazzolà set as an opera (w ...

, Mosè in Egitto

''Mosè in Egitto'' (; "''Moses in Egypt''") is a three-act opera written by Gioachino Rossini to an Italian libretto by Andrea Leone Tottola, which was based on a 1760 play by Francesco Ringhieri, ''L'Osiride''. It premièred on 5 March 1818 at ...

, Otello

''Otello'' () is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on Shakespeare's play ''Othello''. It was Verdi's penultimate opera, first performed at the Teatro alla Scala, Milan, on 5 February 1887.

Th ...

, La donna del lago

''La donna del lago'' (English: ''The Lady of the Lake'') is an opera composed by Gioachino Rossini with a libretto by Andrea Leone Tottola (whose verses are described as "limpid" by one critic) based on the French translationOsborne, Charles 19 ...

'', ''Matilde di Shabran

''Matilde di Shabran'' (full title: ''Matilde di Shabran, o sia Bellezza e Cuor di ferro''; English: ''Matilde of Shabran, or Beauty and Ironheart'') is a '' melodramma giocoso'' (''opera semiseria'') in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to a librett ...

'' and ''Ricciardo e Zoraide

''Ricciardo e Zoraide'' (''Ricciardo and Zoraide'') is an opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to an Italian libretto by Francesco Berio di Salsa. The text is based on cantos XIV and XV of '' Il Ricciardetto'', an epic poem by Niccolò Forte ...

'') took place there in the following three years. Ebers sublet the theatre to Giambattista Benelli in 1824, and Rossini was invited to conduct, remaining for a five-month season, with his wife Isabella Colbran

Isabella Angela Colbran (2 February 1785 – 7 October 1845) was a Spanish opera soprano and composer. She was known as the muse and first wife of composer Gioachino Rossini.

Early years

Colbran was born in Madrid, Spain, to Giovanni Colbran ...

performing. Two more of his operas, ''Zelmira

''Zelmira'' () is an opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to a libretto by Andrea Leone Tottola. Based on the French play, ''Zelmire'' by de Belloy, it was the last of the composer's Neapolitan operas. Stendhal called its music Teutonic, compa ...

'' and ''Semiramide

''Semiramide'' () is an opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini.

The libretto by Gaetano Rossi is based on Voltaire's tragedy ''Semiramis'', which in turn was based on the legend of Semiramis of Assyria. The opera was first performed at La Fenice ...

'', received their British premieres during the season, but the theatre sustained huge losses and Benelli absconded without paying either the composer or the artists. Ebers engaged Giuditta Pasta

Giuditta Angiola Maria Costanza Pasta (née Negri; 26 October 1797 – 1 April 1865) was an Italian soprano opera singer. She has been compared to the 20th-century soprano Maria Callas.

Career Early career

Pasta was born Giuditta Angiola Maria C ...

for the 1825 season, but he became involved in lawsuits which, combined with a large increase in the rent of the theatre, forced him into bankruptcy, after which he returned to his bookselling business.

Pierre François Laporte

Le comte Ory

''Le comte Ory'' (''Count Ory'') is a comic opera written by Gioachino Rossini in 1828. Some of the music originates from his opera ''Il viaggio a Reims'' written three years earlier for the coronation of Charles X of France, Charles X. The French ...

'' and ''Le siège de Corinthe

''Le siège de Corinthe'' (English: ''The Siege of Corinth'') is an opera in three acts by Gioachino Rossini set to a French libretto by Luigi Balocchi and Alexandre Soumet, which was based on the reworking of some of the music from the compose ...

'') had their British premieres at the theatre during this period, and Laporte was also the first to introduce the operas of Vincenzo Bellini

Vincenzo Salvatore Carmelo Francesco Bellini (; 3 November 1801 – 23 September 1835) was a Sicilian opera composer, who was known for his long-flowing melodic lines for which he was named "the Swan of Catania".

Many years later, in 1898, Giu ...

(''La sonnambula

''La sonnambula'' (''The Sleepwalker'') is an opera semiseria in two acts, with music in the ''bel canto'' tradition by Vincenzo Bellini set to an Italian libretto by Felice Romani, based on a scenario for a ''ballet-pantomime'' written by Eu ...

, Norma Norma may refer to:

* Norma (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

Astronomy

*Norma (constellation)

* 555 Norma, a minor asteroid

*Cygnus Arm or Norma Arm, a spiral arm in the Milky Way galaxy

Geography

*Norma, Lazi ...

'' and ''I puritani

' (''The Puritans'') is an 1835 opera by Vincenzo Bellini. It was originally written in two acts and later changed to three acts on the advice of Gioachino Rossini, with whom the young composer had become friends. The music was set to a libretto ...

'') and Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, he was a leading composer of the '' bel canto'' opera style dur ...

(''Anna Bolena

''Anna Bolena'' is a tragic opera (''tragedia lirica'') in two acts composed by Gaetano Donizetti. Felice Romani wrote the Italian libretto after Ippolito Pindemonte's ''Enrico VIII ossia Anna Bolena'' and Alessandro Pepoli's ''Anna Bolena'', both ...

, Lucia di Lammermoor

''Lucia di Lammermoor'' () is a (tragic opera) in three acts by Italian composer Gaetano Donizetti. Salvadore Cammarano wrote the Italian-language libretto loosely based upon Sir Walter Scott's 1819 historical novel ''The Bride of Lammermoor''.

...

'' and ''Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia (; ca-valencia, Lucrècia Borja, links=no ; 18 April 1480 – 24 June 1519) was a Spanish-Italian noblewoman of the House of Borgia who was the daughter of Pope Alexander VI and Vannozza dei Cattanei. She reigned as the Govern ...

'') to the British public. Under Laporte, singers such as Giulia Grisi

Giulia Grisi (22 May 1811 – 29 November 1869) was an Italian opera singer. She performed widely in Europe, the United States and South America and was among the leading sopranos of the 19th century.Chisholm 1911, p. ?

Her second husband was Gio ...

, Pauline Viardot

Pauline Viardot (; 18 July 1821 – 18 May 1910) was a nineteenth-century French mezzo-soprano, pedagogue and composer of Spanish descent.

Born Michelle Ferdinande Pauline García, her name appears in various forms. When it is not simply "Pauli ...

, Giovanni Battista Rubini

Giovanni Battista Rubini (7 April 1794 – 3 March 1854) was an Italian tenor, as famous in his time as Enrico Caruso in a later day. His ringing and expressive coloratura dexterity in the highest register of his voice, the ''tenorino'', insp ...

, Luigi Lablache

Luigi Lablache (6 December 1794 – 23 January 1858) was an Italian opera singer of French and Irish ancestry. He was most noted for his comic performances, possessing a powerful and agile bass voice, a wide range, and adroit acting skills: Lepo ...

and Mario

is a character created by Japanese video game designer Shigeru Miyamoto. He is the title character of the ''Mario'' franchise and the mascot of Japanese video game company Nintendo. Mario has appeared in over 200 video games since his creat ...

made their London stage debuts at the theatre. Among the musical directors of this period was Nicolas Bochsa

Robert Nicolas-Charles Bochsa (9 August 1789 – 6 January 1856) was a harpist and composer. His relationship with Anna Bishop was popularly thought to have inspired that of Svengali and Trilby in George du Maurier's 1894 novel ''Trilby (nove ...

, the celebrated and eccentric French harpist. He was appointed in 1827 and remained for six years at this position. When Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

ascended the throne in 1837, the name of the theatre was changed to Her Majesty's Theatre, Italian Opera House. In the same year, Samuel Phelps

Samuel Phelps (born 13 February 1804, Plymouth Dock (now Devonport), Plymouth, Devon, died 6 November 1878, Anson's Farm, Coopersale, near Epping, Essex) was an English actor and theatre manager. He is known for his productions of William ...

made his London début as Shylock

Shylock is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's play ''The Merchant of Venice'' (c. 1600). A Venetian Jewish moneylender, Shylock is the play's principal antagonist. His defeat and conversion to Christianity form the climax of the ...

in ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'' at the theatre, also playing in other Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

an plays here.

Over the course of the 1840s, Dion Boucicault

Dionysius Lardner "Dion" Boucicault (né Boursiquot; 26 December 1820 – 18 September 1890) was an Irish actor and playwright famed for his melodramas. By the later part of the 19th century, Boucicault had become known on both sides of the ...

had five plays produced here: ''The Bastile'' ic an "after-piece" (1842), ''Old Heads and Young Hearts'' (1844), ''The School for Scheming'' (1847), ''Confidence'' (1848), and ''The Knight Arva'' (1848). In 1853, Robert Browning

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose dramatic monologues put him high among the Victorian poets. He was noted for irony, characterization, dark humour, social commentary, historical settings ...

's ''Colombe's Birthday'' played at the theatre.

In 1841, disputes arose over Laporte's decision to replace the baritone

A baritone is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the bass and the tenor voice-types. The term originates from the Greek (), meaning "heavy sounding". Composers typically write music for this voice in the r ...

Antonio Tamburini

Antonio Tamburini (28 March 1800 – 8 November 1876) was an Italian operatic baritone.Randel (1996) p. 900.

Biography

Born in Faenza, then part of the Papal States, Tamburini studied the orchestral horn with his father and voice with Aldo ...

with a new singer, Colletti. The audience stormed the stage, and the performers formed a 'revolutionary conspiracy'.

Benjamin Lumley

Laporte died suddenly, and Benjamin Lumley took over the management in 1842, introducing London audiences to Donizetti's late operas, ''

Laporte died suddenly, and Benjamin Lumley took over the management in 1842, introducing London audiences to Donizetti's late operas, ''Don Pasquale

''Don Pasquale'' () is an opera buffa, or comic opera, in three acts by Gaetano Donizetti with an Italian libretto completed largely by Giovanni Ruffini as well as the composer. It was based on a libretto by Angelo Anelli for Stefano Pavesi's ...

'' and ''La fille du régiment

' (''The Daughter of the Regiment'') is an opéra comique in two acts by Gaetano Donizetti, set to a French libretto by Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Jean-François Bayard. It was first performed on 11 February 1840 by the Paris Opéra- ...

''. Initially, relations between Lumley and Michael Costa, the principal conductor at Her Majesty's were good. Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

's ''Ernani

''Ernani'' is an operatic ''dramma lirico'' in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, based on the 1830 play ''Hernani (drama), Hernani'' by Victor Hugo.

Verdi was commissioned by the Teatro La Fenice in V ...

'', ''Nabucco

''Nabucco'' (, short for Nabucodonosor ; en, " Nebuchadnezzar") is an Italian-language opera in four acts composed in 1841 by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Temistocle Solera. The libretto is based on the biblical books of 2 Kings, ...

'' and ''I Lombardi

''I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata'' (''The Lombards on the First Crusade'') is an operatic ''dramma lirico'' in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Temistocle Solera, based on an epic poem by Tommaso Grossi, which was "very much a ...

'' received their British premieres in 1845–46, and Lumley commissioned ''I masnadieri

''I masnadieri'' (''The Bandits'' or ''The Robbers'') is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Andrea Maffei, based on the play ''Die Räuber'' by Friedrich von Schiller.

As Verdi became more successful in Italy, he beg ...

'' from the composer. This opera received its world premiere on 22 July 1847, with the Swedish operatic diva Jenny Lind in the role of Amalia, and the British premieres of two more Verdi operas, '' I due Foscari'' and ''Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European traditio ...

'', followed in 1847–48. Meanwhile, the performers had continued to feel neglected and the disputes continued. In 1847, Costa finally transferred his opera company to the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal O ...

, and the theatre relinquished the sobriquet, 'Italian Opera House', to assume its present title, Her Majesty's Theatre.

The appearance of the Black Cuban guitarist Donna Maria Martinez at the theatre in July 1850 was the subject of much attention.

Lumley engaged Michael Balfe

Michael William Balfe (15 May 1808 – 20 October 1870) was an Irish composer, best remembered for his operas, especially ''The Bohemian Girl''.

After a short career as a violinist, Balfe pursued an operatic singing career, while he began to co ...

to conduct the orchestra and entered negotiations with Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sy ...

for a new opera. Jenny Lind had made her English début on 4 May 1847 in the role of Alice in Giacomo Meyerbeer

Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Beer; 5 September 1791 – 2 May 1864) was a German opera composer, "the most frequently performed opera composer during the nineteenth century, linking Mozart and Wagner". With his 1831 opera ''Robert le di ...

's ''Robert le Diable

''Robert le diable'' (''Robert the Devil'') is an opera in five acts composed by Giacomo Meyerbeer between 1827 and 1831, to a libretto written by Eugène Scribe and Germain Delavigne. ''Robert le diable'' is regarded as one of the first grand o ...

'', in the presence of the Royal family and the composer Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sy ...

. Such was the press of people around the theatre that many "arrived at last with dresses crushed and torn, and coats hanging in shreds, having suffered bruises and blows in the struggle". She performed for a number of acclaimed seasons at the theatre, interspersed with national tours, becoming known as the ''Swedish Nightingale''.Headland, Helen ''The Swedish Nightingale: A Biography of Jenny Lind'' (Kessinger Publishing, 2005) The secession of the orchestra to Covent Garden was a blow, and the theatre closed in 1852, re-opening in 1856, when a fire closed its rival. After the reopening, Lumley presented two more British premieres of Verdi operas: ''La traviata

''La traviata'' (; ''The Fallen Woman'') is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi set to an Italian libretto by Francesco Maria Piave. It is based on ''La Dame aux camélias'' (1852), a play by Alexandre Dumas ''fils'' adapted from his own 18 ...

'' in 1856 and ''Luisa Miller

''Luisa Miller'' is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Salvadore Cammarano, based on the play ''Kabale und Liebe'' (''Intrigue and Love'') by the German dramatist Friedrich von Schiller.

Verdi's initial idea for ...

'' in 1858.

From the early 1830s until the late 1840s Her Majesty's Theatre played host to the heyday of the era of the romantic ballet

The Romantic ballet is defined primarily by an era in ballet in which the ideas of Romanticism in art and literature influenced the creation of ballets. The era occurred during the early to mid 19th century primarily at the Salle Le Peletier, Thé ...

, and the theatre's resident ballet company was considered the most renowned in Europe, aside from the Ballet du Théâtre de l'Académie Royale de Musique

The Paris Opera Ballet () is a French ballet company that is an integral part of the Paris Opera. It is the oldest national ballet company, and many European and international ballet companies can trace their origins to it. It is still regarded a ...

in Paris. The celebrated ballet master Jules Perrot

Jules-Joseph Perrot (18 August 1810 – 29 August 1892) was a dancer and choreographer who later became Ballet Master of the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg, Russia. He created some of the most famous ballets of the 19th century including ...

began staging ballet at Her Majesty's in 1830. Lumley appointed him ''Premier Maître de Ballet'' (chief choreographer) to the theatre in 1842.Guest, Ivor Forbes. ''The Romantic Ballet in England'', Wesleyan University Press, 1972 Among the works of ballet that he staged were ''Ondine, ou La Naïade

''Ondine, ou La naïade'' is a ballet in three acts and six scenes with choreography by Jules Perrot, music by Cesare Pugni, and a libretto inspired by the novel ''Undine (novella), Undine'' by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. Pugni dedicated his s ...

'' (1843), '' La Esmeralda'' (1844), and '' Catarina, ou La Fille du Bandit'' (1846), as well as the celebrated divertissement ''Divertissement'' (from the French 'diversion' or 'amusement') is used, in a similar sense to the Italian 'divertimento', for a light piece of music for a small group of players, however the French term has additional meanings.

During the 17th and ...

''Pas de Quatre

''Grand Pas de Quatre'' is a ''ballet divertissement'' choreographed by Jules Perrot in 1845, on the suggestion of Benjamin Lumley, Director at Her Majesty's Theatre, to music composed by Cesare Pugni.

On the night it premiered in London (12 Ju ...

'' (1845). Other ballet masters created works for the ballet of Her Majesty's Theatre throughout the period of the romantic ballet, most notably Paul Taglioni (son of Filippo Taglioni

Filippo Taglioni (aka Philippe Taglioni; 5 November 1777 – 11 February 1871) was an Italian dancer and choreographer and personal teacher to his own daughter, Romantic ballerina Marie Taglioni. (He had another child who also danced ballet, ...

), who staged ballets including ''Coralia, ou Le Chevalier inconstant'' (1847) and ''Electra'' (1849, the first production of a ballet to make use of electric lighting). Arthur Saint-Léon staged such works as ''La Vivandière

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figur ...

'' (1844), ''Le Violin du Diable'' (1849), and ''Le Jugement de Pâris'' (1850), which was considered a sequel of sorts to ''Pas de Quatre''.

The Italian composer Cesare Pugni

Cesare Pugni (; russian: Цезарь Пуни, Cezar' Puni; 31 May 1802 in Genoa – ) was an Italian composer of ballet music, a pianist and a violinist. In his early career he composed operas, symphonies, and various other forms of orche ...